A conversation between Ahmed Shawky Hassan and Huda Zikry.

Written by Huda Zikry.

When introduced as ‘artist, writer, and educator’, German-Uruguayan artist, curator, art critic, and academic Luis Camnitzer replied that he defines himself only as an artist and nothing else and that all his practices in education, activism, research are different mediums he uses to express the way he thinks like an artist. In contemporary art discourse and literature, there is no shortage of the “artist as …” trope, and there are practically no limits to the number of roles a contemporary artist can (or has to) assume throughout their practice. The artist can be an educator, a writer, an activist, an ethnographer, an archivist, an art critic, or an art historian a.o.

The Fire House Cabinet. 2016.

This text attempts to touch upon this theme, not only on how artists find, define, and reconcile these identities and seemingly different practices but also how they incorporate them into a holistic artistic vision, using these practices to inform their art and add dimensionality to their attempts. To ponder these questions, I interviewed Egyptian artist Ahmed Shawky Hassan, on being an artist and something else, on how one finds and defines themselves as an artist.

Fragile Artwork, Do Not Touch. Cite International Des Arts Paris 2017. Photo Ahmed Shawky Hassan.

Ahmed Shawky Hassan was born in 1989 in Ismailia (eg). I know him as an artist, researcher, and writer. He graduated from the Faculty of Art Education at Cairo’s Helwan University in 2011. His practices dissect the ways in which narratives around art are formed, and how these narratives shape the mainstream idea of art. Through texts, objects, videos, and drawings, Ahmed Shawky provides frameworks to examine these invisible and informal narratives. His displays range from the studio to galleries, to museums. He is exploring the roles of the curator, the artist, and the viewer – and how they are complicit in the preconceived assumptions about the space and the artwork.

His recent projects – despite employing different mediums – contain an undercurrent of thinking about the process and contexts of the creation and display of art. They examine the way space and context affect the works of art exhibited in it. Works like: “The Video Museum” – a book on the invisible history of how video art began in Egypt, published in 2020, the ‘Inauguration’ – an exhibition with artist Sherif El-Azma, and the solo exhibition “An Object Resembling an Artwork” in 2017, all embody this concept. In more than one sense, he is the artist as an art historian, the artist as a writer, and the artist as a curator.

Ahmed Shawky Hassan. An Object Resembling an Artwork. TOWNHOUSE GALLERY Cairo 2017. Photo Townhouse Gallery.

Context and Beginnings

HZ: Could you walk us through the beginning of your artistic practice to the way we see it today? How have the concepts and mediums changed and evolved? What are some of the things that you were interested in that no longer interest you?

AS: I have been practicing daily since 2011 (except for 7 months) and continuously thinking of my artistic practice, I remember this specific point, some 10 years ago, I was still a student and practicing traditional oil painting at the time and I was starting questioning what I do. Up to this point, art has been a technical medium that has esthetic qualities, from then, I started rethinking everything I thought I knew.

HZ: Did you struggle to define your art practice? How did you work around this?

AS: One of my turning points was reading Alain Badiou’s ‘Fifteen Theses of Contemporary Art’ and questioning “what is art? Right now, at this very moment and this very place?” and “how is the art I am doing responding to this moment?” I do think the notion of ‘this very moment’ is important. I always had this sense that I started my contemporary practice at a time where a lot of spaces were slowly disappearing, and which escalated over the following decade, but increasingly it was starting to feel like an end to a rather busy era. At that time, I was looking for a way to define the current moment, and this is a long journey in itself.

I slowly moved from painting, exploring with text and research, and the more I asked myself these questions the more it became obvious to me that I had to look for more information, the more I researched, the more questions I found. All of which culminated in this need to produce texts about certain subjects. At this point and for the last five years art has been my full-time job.

The Video Museum Book. Mahrousa Center for Publishing Cairo 2020.

HZ: Upon producing these texts, did you start to think of yourself as a writer?

AS: No, I still don’t consider myself a writer, rather an artist with an interest in text, and because the texts I had produced at this point were completely experimental, they offered this chance where I get to treat the text not as a story but rather as an art object.

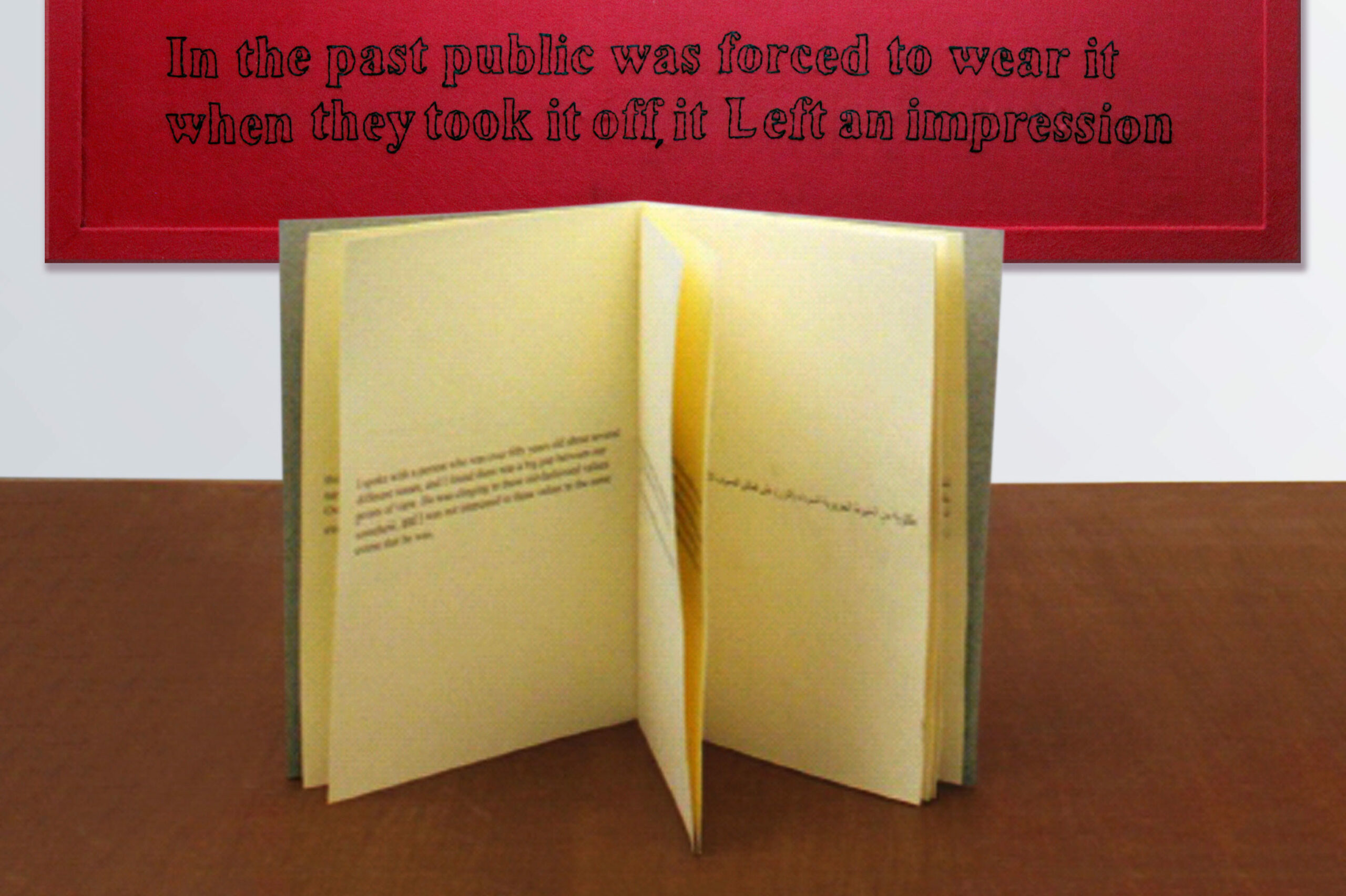

At the time when these texts were being published, I was working on a project called ‘فرض على العامة’ which was my first official departure from painting as a medium and embracing research-based project format. This project takes on a textual format and starting with a conversation with an older man opposing the revolution’s demonstrations, I then proceed to do a little research on this specific generation, and to use the Fez\Tarboosh as the motive to explore their complex relationship to authority.

In retrospect, everything I was doing until 2017 was connected. Long the launch of ‘An Object Resembling an Artwork’ (2017) my research interest solidified, and it continued to the ‘Video Museum’ book, all stemming from questioning one’s position.

Ahmed Shawky Hassan. Public was Forced. TOWNHOUSE GALLERY Cairo 2012. Photo Ahmed Shawky Hassan.

HZ: I want to circle back briefly about art being your full-time job and how that wasn’t easy, I think it is crucial in this sense to discuss the issues with the economics of contemporary art, especially in our context.

AS: Indeed, it could help if we start to think about it through the classic definitions of labor, capital, and commodity. It is straightforward, you produce something, even if it’s your own labor time or energy, and that is what you are paid for.

But what about contemporary art? It is a journey or a process that starts with the production of ideas, then the search for funding with which we can produce those ideas, and if this happens _ which has realistically a small chance and statistically has a success rate of less than 5% _ but given you succeed in securing the funding to produce your idea, next comes production, then distribution and exhibiting are the next obstacles because there is no market. Essentially the proposal is your product, and at this point, the product turns into some sort of foregone conclusion.

HZ: Therein lies the importance of ‘documentation’…

AS: Yes, and I always say, I think that it is time for this system to die, because it is slowly killing us too. Every time you hear back from a funding association, and they mention that they picked 5 to 10 out of 800 applications, I always think of these 800 people, the labor and time they put into writing these projects. And come to think of it, if 800 people got rejected, these 800 people invested 1 to 2 months and will have to start all over again. You could work for a year or two, without making anything happen in terms of production.

Where is the problem then? I would say it isn’t the artist, and it isn’t the funding party. The responsibility lies on all of us to think of ways we can overcome this crisis, the solution isn’t as simple as an increase in funding opportunities or an increase in grants. The solution would be to look for an economic alternative that allows both artists and granting institutions to sustain themselves. We are stuck in the same boat and facing the same situation, there is no escaping this.

HZ: I want to start with your most recent project ‘The Video Museum’: Could you elaborate on your interest in research as an artistic practice that led you to this project? Especially considering the slow shift to text and research you mentioned?

AS: This brings me back to what I was discussing at the beginning: the changes that happened to my artistic practice. My work had slowly gotten to the point where I don’t concern myself with the final product as much as I do with the process. It starts with a personal interest in a subject, an interest that I proceed to relentlessly question. I ask myself why I am interested in this thing and how is it relevant to my situation? What is the need for discussing it? I then move to the question of how and keep pursuing how the subject could present itself.

HZ: And this is where research starts to take form?

AS: Research here is closer to a cognitive model, it doesn’t have a predetermined method but rather creates its method and adapts itself based primarily on my interest in this specific thing and how scarce it is. The bridge between my interest and the scarcity is the research.

HZ: I think this is an entry to discuss how in the introduction of the book, you mention informal art history vs. formal art history. Based on what you said, we can think how this mode of research is based on the scarcity of information and how, in return, the methods it employs have to be informal and flexible. Could you discuss your thoughts on this and the distinction between the formal and the informal?

AS: History is information or knowledge about the past in narrative form, this narrative could be transferred in a book or through another person. The formal narrative is a narrative authorized by an entity that has enough power to spread and instill it. The informal narrative is non-institutional, it is a narrative that doesn’t have the privilege of being widely circulated, and I made up my mind quite early that this is the narrative I want to study and pursue.

HZ: In another conversation, you mentioned a gap, in contemporary Egyptian Art’s discourses, which I think is sensed on so many levels, could you elaborate on this thought?

AS: I have always had an interest in art history and being part of “Muhawelon” really helped me shape and pursue this interest, it was a context that allowed for a free exchange of concepts, and through this project, I discussed several topics that are still of interest to me, around art history and art education. All of which led eventually to the subject of this book, where I was searching for a completely discarded history. From the beginning I knew that I was writing a book on a subject no one knew anything about because I know my sources, some of the things I found were quite literally treated like garbage by some institutions that participate in the making of this history, not to mention individuals.

The question of the gap lies in the answer to the motivation behind the book, my true motivation is from a position of an artist who was looking for a specific piece of information but couldn’t find it anywhere. I decided early on that my whole research process will be reflected in the book because this is the central interest at the heart of the book, which has to do with being an artist in this specific context.

Collaboration and Collectivity

HZ: At the heart of most of your work lies collaboration and centering conversations between artists as catalysts for research and knowledge distribution, or as actual real collaboration on the ground through connecting ideas and artworks. What are your notes on artistic collaboration, collectivity, and artists working together, through your practices and in general, as possible solutions to some of the issues we have been talking about?

Sheif El-Azma + Ahmed Shawky Hassan. SHARJAH GALLERY Cairo (eg) 2019. Photo: Ahmed Shawky Hassan.

AS: I have always been passionate about art collectives and artists working in groups. I want to start by thinking about the artist in the context of a collective: The artist is mostly an unconventional being, someone who isn’t quite comfortable with a routine. I have been involved in several artist collectives and discussed potentials for a lot more that never happened, but at this point, I am starting to believe that is an idea bound to fail.

HZ: Seems a bit radical, why do you think that? Or would rather begin by defining the structure that you think of when you say ‘an artists’ collective or artists working in groups?

AS: When an artist decides to join forces with another artist or two, to achieve together a shared goal that they find hard or impossible to achieve alone. The reason could be economical and financial, or it could be because these artists feel marginalized somehow, and I see this marginalization as a common reason for most collectives to start gathering and working together, it’s what brings people together around a shared goal.

Great, so what happens after the gathering? I’ve had four attempts at collectives in addition to “Muhawelon”, and the collectives never seem to continue working, why is that? First, a collective doesn’t work when the roles aren’t clear, to avoid this you try to assert at the very beginning what everyone’s role is going to be. But later down the line, things get messy, and we can’t seem to separate them, this comes to the issue of equal labor distribution which results in individuals burning out. And because it is a collective, there is no point in individual labor, because whatever someone can do on their own, they should just do on their own. The whole purpose gets defeated. When does a collective work? When everyone consistently achieves its role within the collective, only then can a collective achieve its’ goals.

HZ: I think it’s also worth thinking about how individual works can’t get so far, because even if a collective manages to achieve something, it wasn’t functioning as a collective, it didn’t use the method it set out to use.

AS: For the longest time, I thought a lot about the possibilities of collaboration, I even thought about the possibility of having a sort of syndicate to organize working cooperation. Maybe in some other universe, but never in the conditions we are working under, not when artists are working under such stressful and uncertain conditions.

HZ: What else did you find challenging in working through collectives? You mentioned three reasons.

AS: I would say the artist’s ego is another big reason, and it is very important to come to terms with it. Often, you will find an artist craving the individual aspect of a collective, which beats the whole point. One must ask the hard questions and answer honestly: How much am I willing to work within this group? How comfortable with my name not being on everything I do?

HZ: This point hits home because personally, all my working experience has been with other people, and I have always found the struggle with pinpointing what exactly is it that you do particularly challenging. This also ties in closely with having to participate in the politics of presentation within contemporary art, you must write a biography, write a statement, and constantly describe what you do.

AS: Therefore, the individual must understand and accept their role within the collective. This brings me to my third point, a group must have a flexible structure that is not exactly hierarchical but that still can assign the responsibility of bringing the group together, of maintaining and developing the collective’s methods.

HZ: There is no escape from the necessity of assigning responsibilities, I think.

AS: Yes, and it is not a matter of hierarchy or who will “lead” but rather caring for the need for someone to handle the details that make it possible: you need people to schedule meetings, to handle a budget, to rent a space, and so on. Sometimes, this will be an obstacle facing the collective, either that there is no such person, or the resistance to their existence in the first place because it feels ‘hierarchical’. Which I feel is reductive to the understanding of a group and individual roles.

REFERENCES

Soha Elsirgany: Context as content: Sherif El-Azma and Ahmed Shawky’s dual exhibition (‘Inauguration’) at Cairo’s Sharjah Gallery. On: english.ahram.org. 20 Nov 2019

https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContentP/5/356240/Arts–Culture/Context-as-content-Sherif-ElAzma-and-Ahmed-Shawkys.aspx

ArabCultureFund: Ahmed Shawky Hassan: The Video Museum. 2019.

arabculturefund.org >> 9 January 2022.

Townhouse Gallery: Ahmed Shawky Hassan: An Object Resembling an Artwork. Cairo 2017.

thetownhousegallery.com >> 9 January 2022.

Alain Badiou: Fifteen Theses on Contemporary Art. In: Slavoj Zizek, Jacques-Alain Miller (Ed): Lacanian Ink 22. The Wooster Press Wooster/Ohio (us) 2003.

URL lacan.com/issue22 >> 9 January 2022.