Written by Paola Farran. Published on 1 December 2022.

A few years ago, I found myself standing in front of a huge ‘alien’ plant, embroidered on fabric, constructed out of varied botanical parts. It was accompanied by a text, and both talked very poetically of diversity and adaptation. This artistic installation stayed with me for a while, prompting reflections on current social and political systems, and how they tie in with sustainability issues. Recently, I had the pleasure of meeting with the artists behind this work, Soraya Ghezelbash, and Melika Abdel Razzak, and the opportunity to further explore their practice and their most recent art installation ‘and help our eyes to dance’.

Melika (Jordanian based in Amman) and Soraya (British-Iranian based in Marseille) met in 2015 and quickly discovered their common love for plants and textiles. With embroidery and silkscreen printing, they created their first collective artwork, realizing they both really enjoy the artistic process itself. However, they shared that although the process and the material are important, they are not the only focus. They are especially interested in how the material is connected to the communities that produce it. Textiles are an important medium through which Jordan’s traditional tribes express themselves. This is especially true for the Bedouin women who, through their distinctive embroidery, illustrate their connection to the land and to their natural environment. “They (textiles) really make us reflect on our own sense of roots and belonging,” Soraya explains.

Furthermore, their artistic practice goes beyond the act of creating with a mix of traditional and modern techniques. Through their works, Melika and Soraya focus on identifying an alternate approach to inhabiting the earth, less about consuming it, and more about experiencing it. Through their installations, they seek to draw the audience’s attention to their positions as humans within ecology and inspire a reflection on how that relationship can evolve.

Photos: Abdel Razzak Gheselbash.

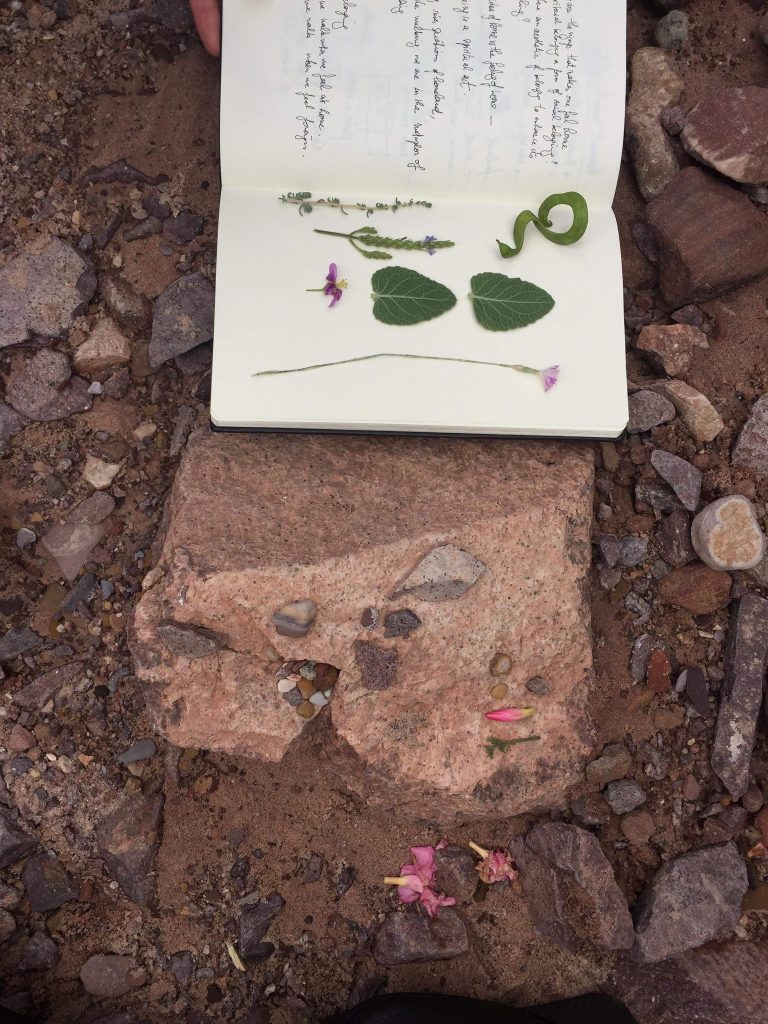

The tandem addresses their study on ecology in a sensorial fashion, not relying solely on scientific data. For example, when studying plants, their habitats, and behaviors, Melika and Soraya do not approach them merely by studying botanics, but regard them as an integral part of humanity. On my question about their relationship with plants, they shared, “It has to do with us wanting to be also connecting to the earth, connecting to the ground, where we are, where we go and that’s like, the most direct kind of connection we can see, and feel, and be with.” It was interesting to discover their outlook when picking plants to study: what I would consider a lack of respect for nature, they see as a survival gesture that allows them to connect with themselves and reach a better understanding of nature. The way they described it to me if you only study nature with an empirical eye, “…you are remote from it, and you are consuming it, whether it’s gathering information, spending time in a natural park, or entering a flower shop. These are all methods of consumption. The idea is to move away from that approach where nature doesn’t become transformed by human activity, but human activity becomes an inherent part of it, an element in the same way air or water, or plants are.”

And here’s the interesting quirk in their approach: as they explore the nature of the relationship between people and the environment, the artists accept the fact that ecology today does not comprise natural elements alone, but that manufactured objects, the traces of our presence on earth, are now an intrinsic part of it. This took me on a quest to find definitions for ecology and nature, which, I discovered, are multi-faceted and still not agreed upon. Scientifically, ecology represents the interaction of living organisms with each other and with the environment. Can made-objects be part of this system? Their interaction with the environment is undeniable, and they are a stark manifestation of the human relationship with nature. If tackled from an ethical perspective though, this relationship is complex and can have different motives (moral, utilitarian, empirical, aesthetic…). And as the modern ecophilosopher Boreiko puts it, the ethical relationship of man with nature should take into account “the perception of nature as a member of the moral community, […] the equal rights and equivalence of all life, as well as the limitation of human rights and needs.” So do manufactured objects infringe on those equal rights? Are they a manifestation of human excesses?

Melika and Soraya look at it from the human’s perspective: when considering nature’s cycle from, and back to, the earth, one cannot deny the existence of what they dub as the ‘man piece’: the fabricated object inserted into ecology by humans. “So how do we connect these two things (objects and nature) together? We have to invite movement, so we can feel like we, humans, go into the cycle – are part of this cycle of life and death.”

Along those lines, the artists’ definition of nature is not just the wilderness where fauna and flora are abundant but includes its manifestations within the human environment, be it urban or rural. In fact, their first artwork, ‘diversity or death’, documented the species of plants surviving in Amman’s neighborhoods. They ‘followed’ them and mapped a route in the city, and discovered there were many invasive species that were not tended to, and were left to take over empty or abandoned lots. Those were destroying indigenous varieties of plants, as well as compromising the ecological equilibrium of some areas. Through botanical research, Melika and Soraya studied the plants’ properties and the impact they have on their new environment, their capacity to adapt, merge, and reinvent themselves and eventually become native. The research also revealed that it takes a thousand years for a plant to be considered native to a region. These findings echoed questions of migration, adaptation, and assimilation. When I asked them what parallel they saw with migration, Soraya explained, “This research brought forth the concept of diversity, drawing a parallel for the need for diversity in our societies too… The idea here is not to merely adapt, but to also transform the genetic heritage…And like, the kind of rules, these rules of integration, for instance, and of settling that apply to plants, actually completely apply to human beings. ”

These findings translated into an installation, very representative of the artists’ approach to creating experiences rather than art pieces. The installation combined a variety of works: parts of plants on textiles, both originating from the areas they explored, ‘healing potions’, and poetry. The idea was to immerse the audience in an imagined landscape, focused on bringing people closer to nature and questioning the idea of belonging.

Melika and Soraya’s installations usually involve a sensory element, where viewers become actors; seeing, touching, and tasting. The artists bring their audience to “really see” the plants, not only as an aesthetic material, but as a source of understanding and healing, and one of life. They offer, for example, drinks from the flowers they have studied, or seeds to be collected and replanted by members of the audience. Adding depth to the work is a ritualistic approach that, I feel, automatically draws us closer to the land, reminiscent of the relationship our ancestors had with nature, extracting what they needed from it, but offering back respect and care. The artists’ objective is to plunge us into an atmosphere that forces us to reconsider our perception of nature and reflect on the role we play as part of ecology, as well as the relationships we develop with the earth and the land.

In their more recent artwork, the artists tackle what they described as the ‘ecology of senses’, inviting an approach to nature that is spontaneous and uncalculated. In an installation that manipulates cross-cultural media, ranging from very fine handmade botanical collages to loud and bright LED signage, they again lead the audience to reflect on their role as part of nature. Melika describes the installation to me, “We are using modern tech or commercial objects, using those techniques to invite them to come and look at this piece, invite them to consume something, but in the end, they find themselves connecting to their environment, to their own nature.”

True to their approach, Melika and Soraya do not put emphasis on the physical artworks. In most cases, these lose their materiality or find new homes by the closing of an exhibition. For them, the process, described as a personal journey, is as important as the work. And the installation itself is viewed as a performance – one played by the audience as they interact with the materials. In that sense, they also feel the artist plays no role in how the audience experiences the installations, as reactions can range from a superficial appreciation of the aesthetics to a much deeper questioning of current practices. Even if they downplay this aspect, I feel the importance of their work lies in creating a setting that, in addition to initiating dialogue, finds the right sensorial means to drive the viewer beyond a rational take, and towards a deeper reassessment of one’s views on nature and their role as part of it.

When I asked them, “… and where do we go from here?” Melika thought it was important “.. to find balance, to a better equilibrium with nature, to work with whatever we have instead of making excess objects, materials, etc…” and Soraya added, “to repeat the same message, over and over again, to become more connected to our surroundings, and to be in peace.” Our conversation was rich and inspiring. If I were looking for concrete solutions to ‘fix’ everything that’s wrong with the world, I wouldn’t find them in their delicate, thoughtful artwork. What I do find though is a call to reconnect with the soil, to consider myself as an innate part of nature, and be aware of the ecological ripples my every action causes.